Digital Decoupage

Digital Decoupage, the second aesthetic experimental course promoted by CRIT-AADE, was developed by Professor Jen-Hwang Ho from the Graduate Institute of Architecture at NYCU. This course follows a three-stage process, progressing from observation to digital image manipulation, and culminating in creative interpretation.

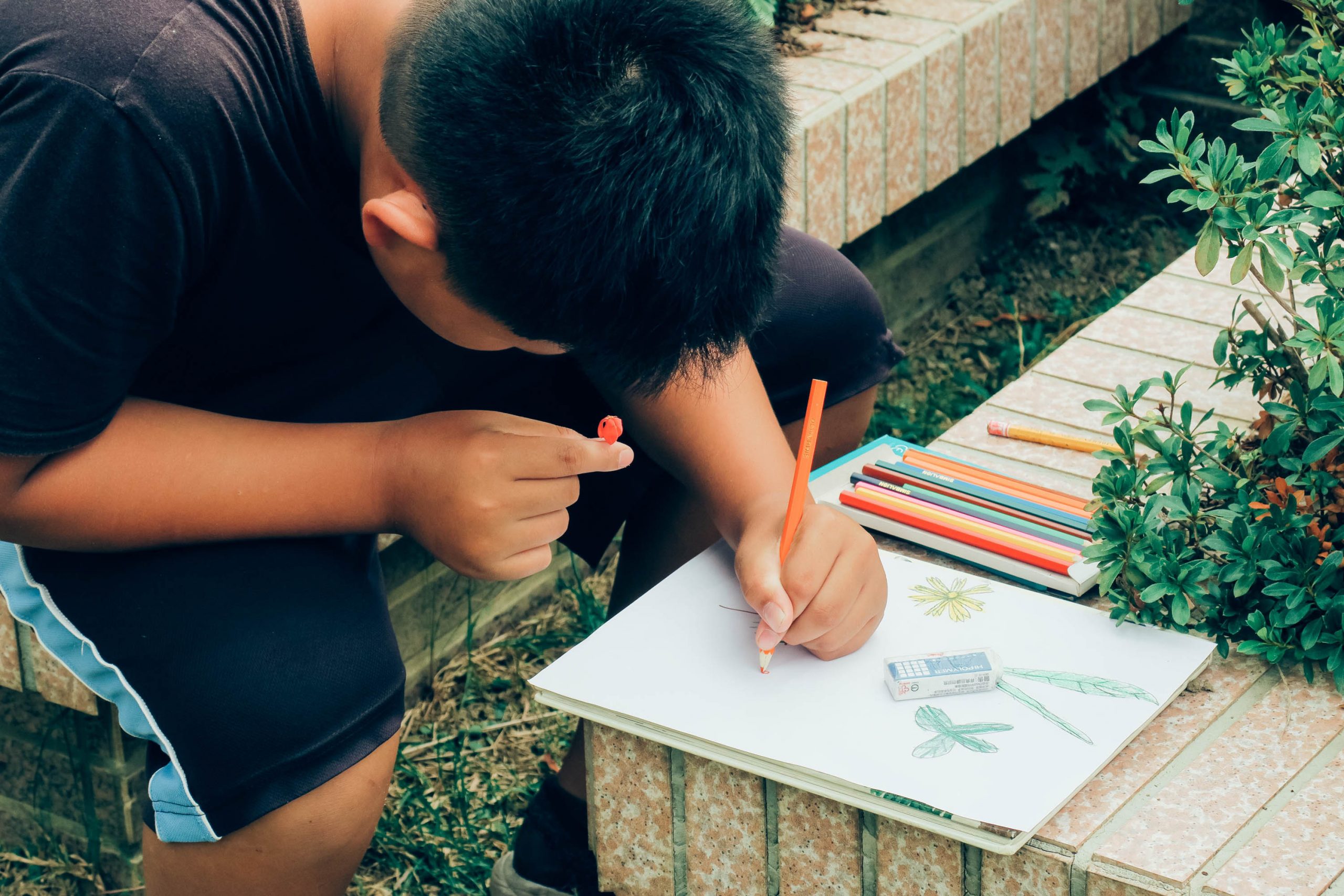

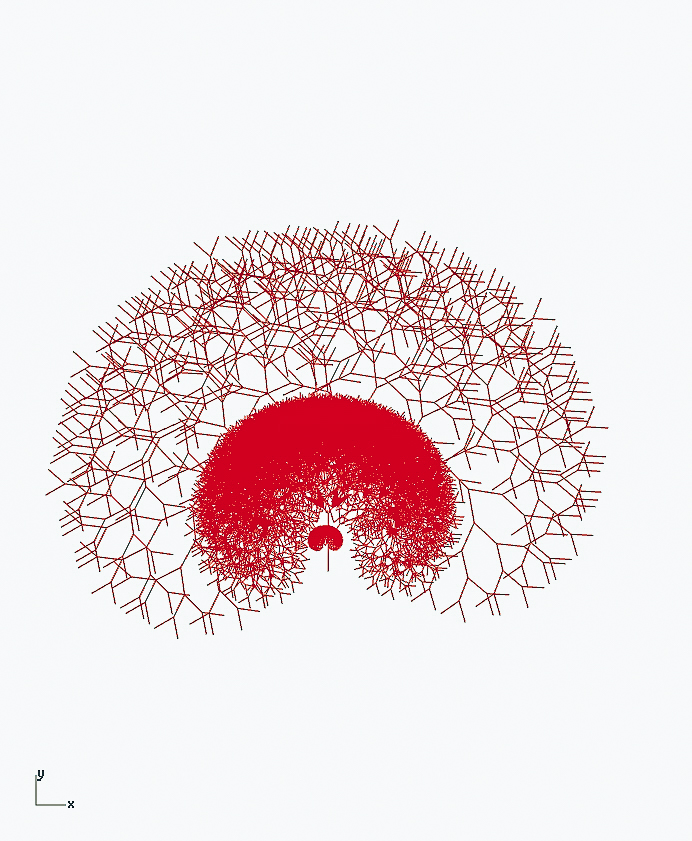

In the first stage, students explored the campus flora, observing patterns in flowers, leaves, veins, and branches. They documented their findings through photos, sketches, or frottage imprints, demonstrating their understanding of natural science and geometric logic. In the next stage, students were introduced to digital modeling and visual programming using software such as Rhino 3D and Grasshopper. With simple preset procedures, they generated solid geometric forms like polygons, pyramids, and spheres, visualizing the mathematical order inherent in natural forms. This stage highlighted that, with fundamental algorithmic knowledge, one can create a variety of organic shapes. The students then compared these digitally generated forms with their initial observations. They also utilized laser cutting, 3D printing, and other technologies to produce real objects from their digital designs.

Traditional environment familiarity courses typically start with naming and identifying objects within a specific setting. However, this approach often limits perception to mere identification. In Digital Decoupage, students were encouraged to delve deeper into the meanings behind names. Regardless of whether they knew the plant’s name, they could still observe its geometric structure and organic order. These observational “filters” opened up new possibilities for aesthetic perception beyond simple identification, fostering further creative manipulation and interpretation.